Growing up in Lowndes County, Alabama, Catherine Coleman Flowers learned the ropes of civil rights organizing and witnessed firsthand what she calls “America’s dirty secret” — a widespread lack of access to basic plumbing and sanitation in poor, rural communities, many of whose residents are (like herself) the descendents of enslaved people.

Today, Catherine is an environmental and climate justice activist focused on increasing access to working sewage and water systems in Black, Indigenous, Latinx and poor rural communities across the U.S., where waste treatment infrastructure is increasingly failing due to systemic inequity, underinvestment and extreme weather driven by climate change.

As the Founding Director of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice, Catherine Coleman Flowers works to eliminate the health, economic and environmental disparities impacting rural and marginalized communities, and serves as the Co-Vice-Chair of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. She was recently recognized in Forbes’ 50 Over 50, and named as one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People of 2023.

As an Elemental Policy Lab Fellow, Catherine is bringing earth and space scientists at NASA together with elected officials and community leaders from vulnerable communities to develop policy recommendations on sustainable rural wastewater treatment. We hosted Catherine in Hawai’i recently for a conversation about environmental justice, and to learn more about the momentum she’s seeing on the local and federal levels to address this issue.

• • •

Who inspired you to do this work, and how did you start focusing on wastewater issues?

I was blessed to be born to two very inspirational parents who never saw a problem they didn’t want to fix. Lowndes County sits between Montgomery and Selma, and it is the birthplace of the original Black Panther party. I grew up surrounded by people who were deeply involved in the Civil Rights Movement and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. It was the best education in activism I can imagine and put me on the path to becoming a social justice advocate. I never expected that wastewater would become my primary focus, but I learned from those around me that some of the most important activism starts at home, in community with your neighbors.

While working in economic development in rural Alabama in 2002, I saw people being arrested in my home county of Lowndes for having raw sewage on the ground due to failing waste disposal systems and septic tanks. I’ll never forget one visit we made to a home in Lowndes, where we saw raw sewage running down the road before we even saw the home. Another time, we met with a minister who could no longer hold services at his church because they did not have a functioning septic system. In another house, both the husband and wife had been arrested for not having an adequate septic system.

Even then, I didn’t realize the full extent of the problem, until we conducted a house-to-house survey and saw just how bad the situation was and saw how many other aspects of life can be impacted by wastewater issues.

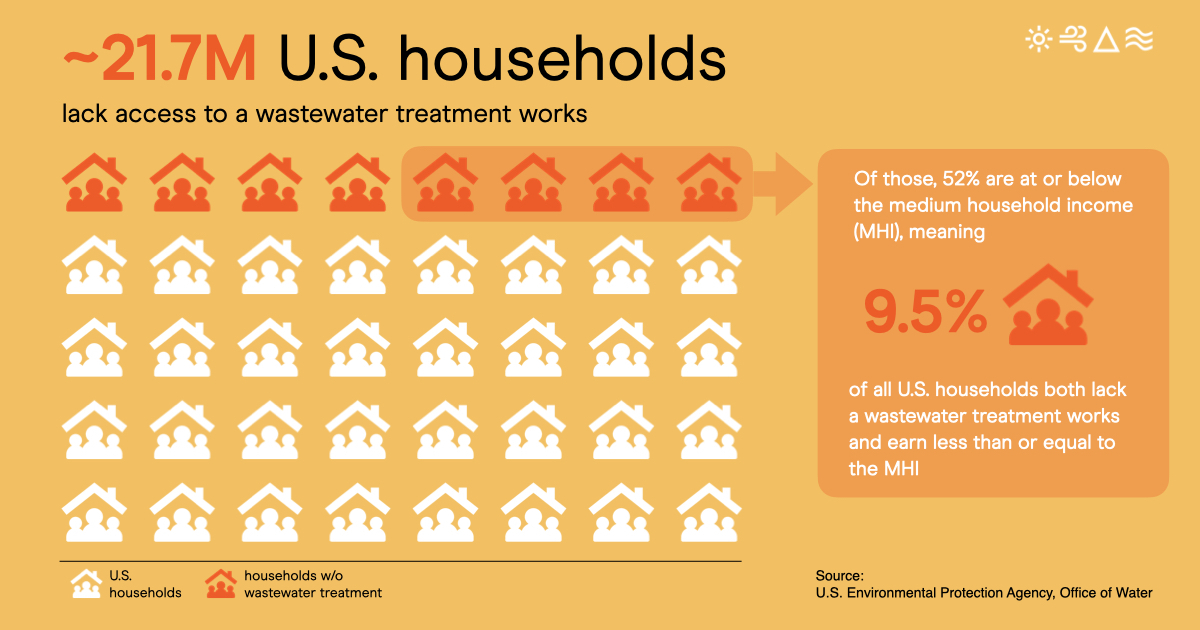

As we started talking about it and bringing national leaders to Lowndes to bear witness, people began reaching out to us from other parts of the country. That’s when I learned that this problem isn’t unique to Alabama, the South or even to only rural communities — it’s a very significant, national problem.

How does the issue of sanitation extend beyond rural Alabama to other communities across the U.S.?

The longer I have done this work, the more obvious it has become that environmental injustice and sanitation inequality impact people all over the country — not just in rural communities in the South. This issue exists in white communities in Appalachia, on Native American reservations, in the Central Valley of California, in suburbs north of New York, in southern Illinois.

I’m sure there are countless more communities where people don’t necessarily talk about the problem, which is why I’m so hellbent on discussing wastewater and removing the shame from what I call “America’s Dirty Secret. To live with raw sewage in your backyard, where your kids should feel free to play — it’s not a problem that should afflict so many people in the world’s richest country.

My foundation, the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice, did a study a few years ago — in partnership with the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor’s College of Medicine — which revealed the presence of tropical parasites that are endemic to developing countries. We found several parasites — including hookworm — that were thought to have been eradicated from the U.S.

I fear that unless we do something about it, the next pandemic will come from a rural community here in America.

You’re focusing on underserved and largely rural communities — tell us more about the importance of centering the experience of those who live outside of corridors of power and access to infrastructure/resources?

I strongly believe solutions to deeply rooted problems in this country lie within the communities themselves — especially when it comes to environmental justice. We’ve seen time and time again throughout history the failure of “solutions” that don’t factor in the true lived experience of those experiencing the issue.

And since I come from an “underserved and largely rural community,” my experience growing up was centered far outside of the traditional corridors of power. I know first-hand what it is like to be outside of the institutions that are supposed to be serving all Americans.

I’ve also spent many years in cities — from Washington, DC to Detroit to Huntsville, where I live now — and in recent years have been invited into a few “corridors of power,” so to speak. And I do think that, while progress can feel slow, things are changing for the better. The internet has made it easier for people living in poor, rural communities to share their experience, which I know is foreign to so many urban Americans, especially many reporters and politicians. National media outlets have been putting more resources into reporting from rural communities, and anyone can read reporting online directly from the local outlets themselves.

President Biden’s administration is working hard to lift up voices that haven’t been heard before, and I’ve been honored to serve alongside so many of them on the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council (WHEJAC). We all know that environmental justice issues disproportionately impact marginalized, low-income, communities of color, often in rural communities. It is one of the WHEJAC’s central tenets that we center the experiences and voices of those outside of Washington.

What do you think needs to change to enable systemic change in the sanitation?

We need community input, and consistent accountability from the national and regional governments in checking up on the solutions implemented and making sure they are actually serving the community.

I’m focused on ensuring no one is criminalized for their wastewater system failing and implementing warranties on septic systems. There is a lack of accountability because there’s not an independent group to make sure these systems work. The burden isn’t on those putting in the waste removal systems — it’s entirely on the families using them. And if the systems fail, and it is reported to the authorities here in Alabama, the families can be cited, brought to court or even arrested. The problem works to criminalize poverty because the people who have been cited for dumping raw sewage have generally been poor people. They are often cited over and over and over again. The cost is unbearable for many rural Americans.

Another priority for me is exploring new technologies. If we can process human waste on the international space station, perhaps NASA can bring their cosmic findings to solutions here on earth.

You have been working on these issues for many years — what is new about this moment?

Someone years ago warned me that it would be impossible to get attention on the wastewater crisis because it’s unsavory, but thankfully that hasn’t been the case. We’ve made huge strides in the past few years garnering focus on these issues at a regional and even national level.

And national attention can be vital — think about voting rights, for instance. Even though everyone had the right to vote, it took federal intervention in the form of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 for many people to be able to exercise that right. I believe that living with safe water and functioning sanitation systems is a right for all Americans, and I’ve been impressed by the steps the Biden-Harris administration have taken to address this issue at the federal level.

Last summer, Lowndes County hosted EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and White House Infrastructure Coordinator Advisor Mitch Landrieu for the announcement of the Closing America’s Wastewater Access Gap Community Initiative. This pilot program will allow the EPA and USDA — in close collaboration with 11 local communities, state and Tribal partners and on-the-ground technical assistance providers — to leverage technical and financial expertise to make progress on addressing the wastewater infrastructure needs of some of America’s most underserved communities.

This is an unprecedented level of resources and dedication being paid to this issue, and I’m excited to see what solutions will come.

• • •