The Elemental Policy Lab Fellow is working with rural leaders and electric cooperatives to accelerate federal funding implementation.

Picture this: It’s 1937, and more than half of all American households have had electrical power since 1925. But you live on a farm in rural Georgia where investor-owned utilities refuse to incur the costs of installing electrical lines to your sparsely-populated county, cutting you off from the financial and cultural benefits of the electrical revolution.

So you and your neighbors take things into your own hands and petition to charter an electric cooperative, or member-owned utility. In March 1938, with a $200,000 loan made possible by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Rural Electrification Administration Act, your cooperative installs the first 169 miles of line for 329 households.

This is the true story of the Central Georgia Electric Membership Corporation and echoes that of many other electric cooperatives formed by rural communities to build out their own energy infrastructure when investor-owned utilities left them behind.

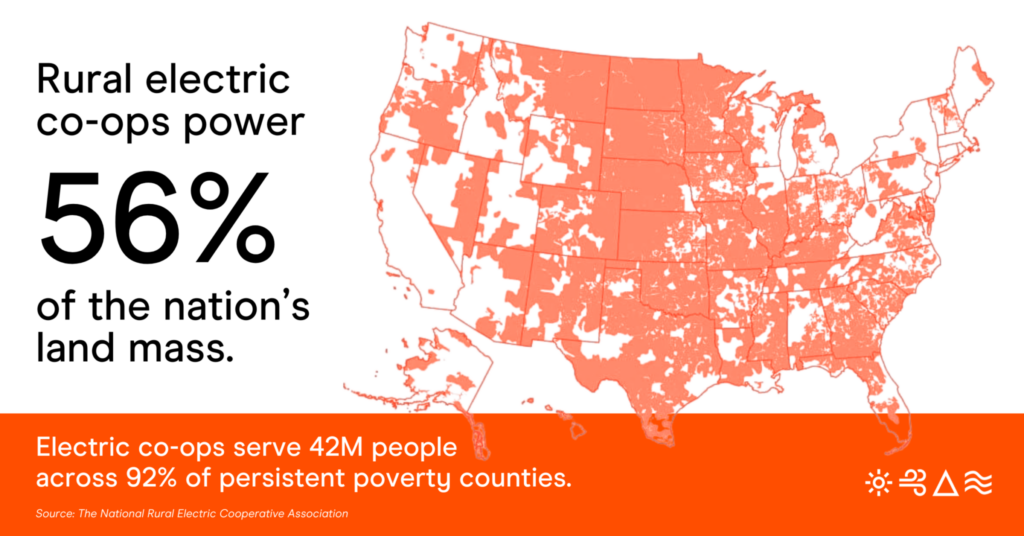

Today, these community-owned utilities provide electricity to 42M people living on more than half the U.S. landmass, including 92% of persistent poverty counties, which are counties where at least 20% of the population has lived at or below the poverty rate for 30 or more years. While many electric co-ops still rely on coal power, their democratic structures mean member-owners hold sway in advocating for change and embracing clean and resilient energy sources.

This is why Elemental Policy Lab Fellow Frances Sawyer is building on her work to support rural leadership in the clean energy transition by developing and implementing deployment tools for rural electric cooperatives ready to embrace clean technologies. Frances, who leads Pleiades Strategy — a firm advising mission-oriented organizations on strategy, policy and campaigns — also serves as a senior advisor to Climate Cabinet Action helping local leaders run, win and legislate on the climate crisis.

This is why Elemental Policy Lab Fellow Frances Sawyer is building on her work to support rural leadership in the clean energy transition by developing and implementing deployment tools for rural electric cooperatives ready to embrace clean technologies. Frances, who leads Pleiades Strategy — a firm advising mission-oriented organizations on strategy, policy and campaigns — also serves as a senior advisor to Climate Cabinet Action helping local leaders run, win and legislate on the climate crisis.

We spoke with Frances to learn more about the history of electric co-ops and why this moment presents an unparalleled opportunity for rural clean energy adoption.

How did you first learn about the problems co-ops and rural communities face when it comes to energy infrastructure?

I personally got involved in rural electric cooperatives as a young kid because the Rural Electrification Act (REA) was signed about 15 miles down the road from where my grandmother grew up in Greenville, Georgia.

The REA, which was one of the core New Deal programs, created a concentrated push to make sure that every household, every farm, had access to electricity. Rural electric cooperatives were the community-owned utility type that came about as a means of solving this problem. The cooperative model brought transformative electricity to rural America by bringing together local self-reliance and federal financial support. In a way, the early REA days are a model for where we are today with new investments through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA): we have significant federal resources ready and able to support local community-led action on clean energy.

How do rural electric co-ops factor into the Justice40 initiative to deliver the benefits of climate, clean energy and other investments to disadvantaged communities?

Cooperatives have a central role to play in reaching Justice40 initiative goals, as they disproportionately serve disadvantaged communities, including those burdened by generational pollution and left behind by the old economy.

Rural electric cooperatives serve 92% of persistent poverty counties, and some of the highest energy burdens are in areas served by cooperatives. You may see up to 30% of a household’s total income going to their energy bills. There are families who are literally trading off whether they’re going to pay their power bill, medical bill or keep food on the table. So when we think about a clean energy transition, we have to reach these communities that have the highest energy burdens.

And these are diverse communities. When we talk about rural America in political shorthand, a lot of folks envision a whitewashed, 1950s-style TV America. But rural America is diverse and becoming more diverse by the year.

Many rural communities of color have infrastructure needs that have never been fully met — and have a disproportionate energy burden relative to their white peers. Cooperatives have a role to play in leveraging new federal funding to address these disproportionate burdens.

Looking not at the household program level, but the generation fleet level, co-ops have an additional opportunity to deliver on pollution reduction. Co-ops have some of the dirtiest power left on the grid. This was, in large part, caused by a policy choice: until the IRA, co-ops could not directly access the tax credits for wind and solar while maintaining community ownership. So they fell behind. Co-ops still get about 32% of their power from coal, as compared to 19% for investor-owned utilities. So as we look at particulate pollution and community health benefits that come from moving from coal to clean — co-ops are overdue in the energy transition.

What’s the energy like in the community right now because of the incentives and funding available at the federal level? And what do we need to do to make sure those investments get to the right places?

It is absolutely exciting. Having worked in and around co-op policy for a number of years, this is the investment moment. Through the IRA, this is the largest investment in rural electrification since the New Deal in the 1930s. We now have huge buckets of capital — including $11B out of the Empowering Rural America (New ERA) Program, which is run through the Department of Agriculture, as well as access to the tax credits in the IRA — that this segment of the utility sector has not seen in a very, very long time.

What we see now is capacity building needed across the board. We worked really hard all summer with a number of partners to get the word out about the New ERA program. And we had really big conversations about the portfolio of clean energy technologies that an electric co-op could turn to — in terms of how energy is managed, where generation comes from, where those projects are sited and the scale of those projects. Because largely you have folks moving from a relatively simple system, in which there are central coal fire and gas fire generators, to a much more diverse portfolio of technologies. There’s a huge amount of education involved here.

And, there is a lot of demand. USDA saw 157 proposals from cooperatives in nearly every state representing $93B in public and private investment. These proposals tallied more than 750 clean energy projects, and half of all proposals described projects that would serve distressed, disadvantaged, tribal or energy communities. Not all of these projects can be supported by New ERA — but all represent potentially transformative projects that can be brought to life in rural America to advance the clean energy transition.

We’d love to hear more about what you see as the opportunity and need for innovative technology, new business models and other systems change for Rural Electric Co Ops and rural energy users.

Rural energy systems have so much to benefit from new innovative technologies. At the heart of it, a rural electric cooperative on average serves just over seven customers per mile of wire they string. An investor-owned utility, on the other hand, serves over 30 people per that same mile of wire. So when you’re providing power to a more decentralized and distributed network your infrastructure is stretching farther, and being asked to do more. In a changing climate, the pressures that are faced by those miles of wire and those systems are mounting.

All of these technologies that folks in the Elemental network and folks across the clean technology landscape have been developing — grid edge resources, energy management, electric vehicles, distributed storage, electrification of buildings — all of these tools become more meaningful when you have fewer people per mile of wire that a utility serves. Clean, cost-cutting, modular systems can benefit both member-owners and the utilities.

That opens up a huge door for cooperatives to adopt these technologies and really showcase what these systems can do, in terms of keeping costs as low as possible and serving their customers in the best, most resilient way possible. Co-ops were really ahead of the curve in getting advanced smart meters deployed for this exact reason. They have every impetus in the world to give the best value to their member owners who own and direct and have a stake in the utilities themselves to capture and lead on clean energy technology.

• • •