Photo ©Wellington Imagery courtesy of Carbon Removal Canada

Canada’s stunning coastline is the longest in the world, at approximately 151,019 miles — equivalent to road tripping from Northern California to Maine roughly 53 times. In 2022, an estimated 600,000 people were exposed to rising seas along these coastlines.

And while Canada’s coast faces countless climate threats, Elemental Policy Lab Fellow Na’im Merchant said it also could become important for climate resiliency as an unparalleled resource for ocean-based carbon dioxide removal (CDR) methods. When combined with other CDR methods that tap into Canada’s vast and diverse landscape, and lean on its abundant clean energy supply, skilled workforce and rich Indigenous knowledge, Na’im said his home country is uniquely positioned to play a major role in scaling CDR. That is, if policymakers and innovators act quickly and equitably.

Na’im, who previously worked with Last Mile Health and the Clinton Health Access Initiative to address social and health inequities in Liberia and Malawi, recognized climate change would exacerbate these global inequities and turned his attention to work on CDR to fend off — and one day reverse — its harmful effects. Since 2020, he has advised governments, companies and nonprofits on scaling the impact of carbon removal solutions.

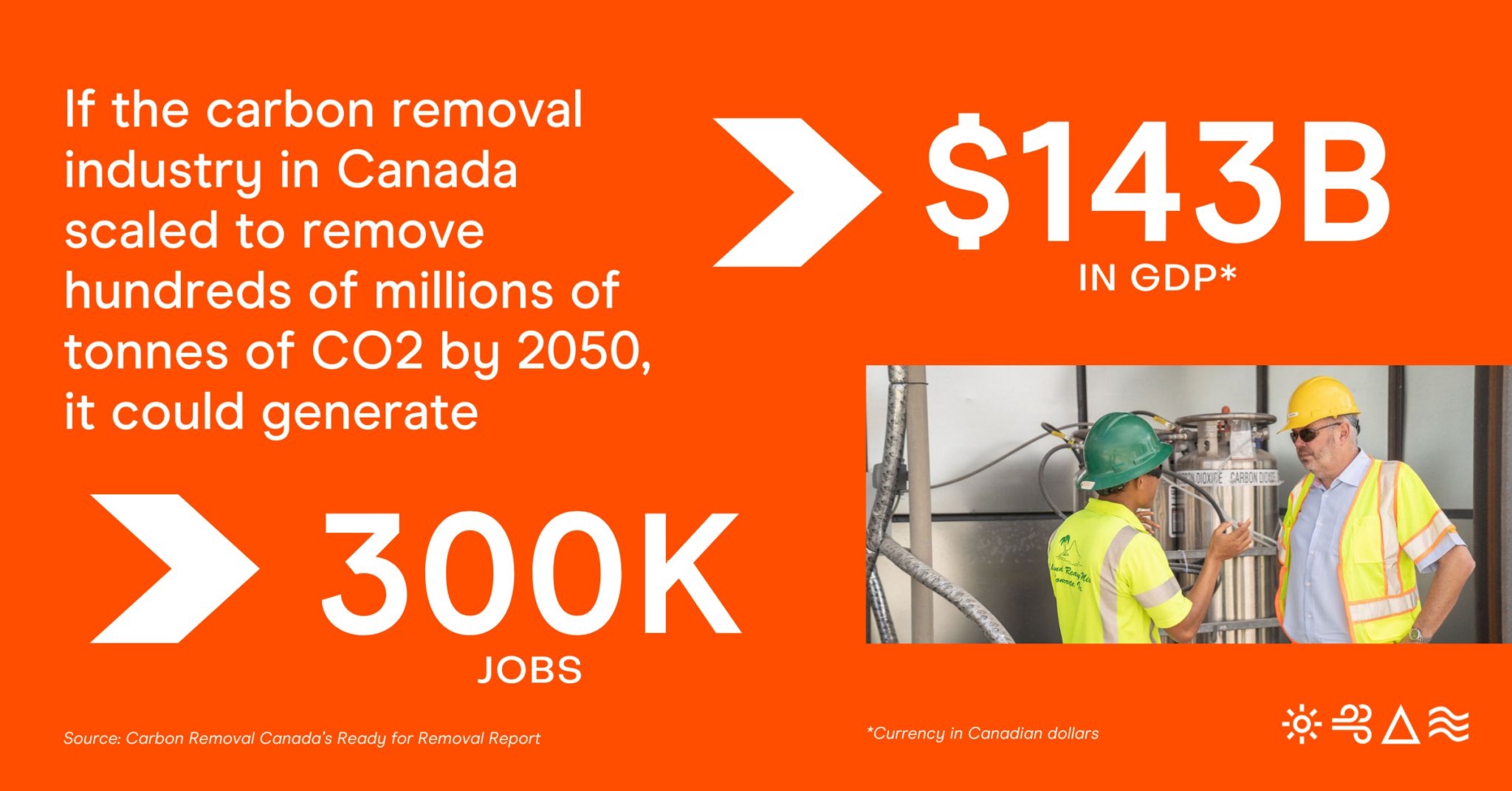

In November, Na’im officially launched the independent policy initiative Carbon Removal Canada concurrently with publishing the Ready for Removal report, aimed at developing and advancing a shared policy framework for scaling equitable CDR in Canada. As an Elemental Policy Lab Fellow, Na’im is working with a diverse set of stakeholders, including Indigenous leaders and innovators across Canada’s First Nations, to inform Carbon Removal Canada’s policy recommendations — an approach he hopes will become a blueprint for other countries.

We caught up with Na’im to hear more about the who, how and the why of CDR in Canada — and how Indigenous engagement and ownership is key to moving this work forward globally.

• • •

What was that ‘aha moment’ that led you to carbon dioxide removal and how does it connect to your previous work in public health?

The “aha” moment for me was realizing the necessity in carbon dioxide removal (CDR) to address our legacy emissions. We’ve emitted close to 1.5 trillion tons of excess CO2 into the atmosphere since industrialization, so even if we stop emitting CO2 by 2050, the planet won’t just cool right down. We’ll be locked in to whatever temperatures we’re experiencing when we get to zero. And that could be really bad — especially for many countries in the Global South.

My previous career in public health had me working and living in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa that would be worst impacted by climate change — and indeed are facing these impacts very acutely today. That made me realize that while getting to net-zero by 2050 is an important milestone (and CDR can help with that, by the way), it’s not the end game. The world needs to go net-negative, and not enough people are paying attention to that.

Your initiative Carbon Removal Canada recently released a report focused on advancing carbon dioxide removal policies in Canada. So — why carbon dioxide removal? Why Canada? And why now?

CDR is going to be absolutely critical to addressing climate change, especially in the decades ahead. Even though CDR’s role will be more relevant in 2050 and beyond and our immediate attention must focus on reducing emissions, we won’t be able to flip a switch and expect at-scale CDR to just be there when we need it.

Creating an industry that removes massive volumes of CO2 from the atmosphere is a huge undertaking and there’s an opportunity for Canada to build this industry from the ground up that focuses on how Indigenous and rural communities can be at the forefront of building and sharing in the gains of that new industry.

There’s an opportunity for Canada to build this industry from the ground up that focuses on how Indigenous and rural communities can be at the forefront of building and sharing in the gains of that new industry.

I think Canada is really well suited to contribute to global efforts to scale up CDR. Canada has the natural resources, technical know-how and political will to build a thriving CDR sector — we just need to embrace it. We also think Canada can be a test bed for innovation in policy and technology, and we can export what we learn to other countries and have an indirect impact that way.

The challenge is that we don’t have any commercial CDR capacity today in Canada. We need to start building now. We need to start learning what works and what doesn’t. We need to deepen our skills in how to engage communities and build high integrity projects. We see this decade as a critical, formative decade for CDR because of all the learning we have to do. And that can’t happen in the lab, we need more proof-of-concept efforts around CDR in Canada.

What inspiration or lessons did you take from your career for how to approach CDR policies? What do you think policymakers and advocates beyond Canada might learn from your research and approach?

One piece of inspiration from my previous career that I think could be adapted for CDR is the use of innovative financing approaches to scale-up access to HIV medicines and vaccines — critical public goods. About 20 years ago, countries and major global funders got together and created advance market commitments (AMC) to shape the market conditions needed to manufacture and distribute these life-saving health products in high-need countries around the world. Almost a billion children have been vaccinated, for example, thanks to these efforts. Similar financing mechanisms could be used to scale-up another public good — CDR. We’re starting to see that in the voluntary carbon market today, but the opportunity to do even more is immense, especially by leveraging public sector resources.

We’re hoping that policymakers outside of Canada can benefit from what we learn over the coming years on embedding Indigenous participation and ownership of CDR projects into the CDR deployment model. We’re at the very beginning of that journey, and we’re learning from a number of people, but a big question we’re trying to answer is — how can we approach building a CDR industry that is truly inclusive of communities that have been ignored in the past? By centering that question early on, I’m hoping we’ll learn a lot, and be well positioned to share that with groups asking similar questions beyond our borders.

Tell us about your process for community engagement and help us understand the various stakeholders you involved in your research. What did you learn about how to responsibly and effectively incorporate community engagement to craft carbon removal policies that promote inclusive economic gains?

Right now our process is just focused on listening and learning. We engaged an Indigenous-led consulting firm that has guided us in conducting listening sessions with Indigenous leaders and non-Indigenous scholars over the last several months. Some of the key themes we’ve learned include: (1) the importance of direct consultation at every step of deploying new CDR projects, (2) that projects should involve opportunities for equity and co-ownership with Indigenous communities, (3) that we need to think about long-term benefits from a project that extend beyond the project’s lifecycle, and (4) the importance of addressing barriers to participation for Indigenous-owned businesses within the emerging CDR industry.

We’re now working on what each of those things mean more specifically for responsible deployment of carbon removal projects and how we can embed those into guidelines and policies geared toward scaling up CDR in Canada. We know we need to go beyond community engagement and think about community equity, participation and ownership. I think we’ll be continuously learning and hoping to share what we learn every step of the way — within Canada and beyond.

What drew you to working with Elemental as a Policy Lab Fellow, and what are you working on now?

What drew me to Elemental was the focus on community and equity. There was clear alignment with Elemental’s ethos on the need for climate solutions to address existing inequities, and the power of community to solve problems. I think that deep values alignment played a huge role in drawing me to Elemental — and I’ve been able to better embed those values into my work as a result.

• • •